McDonald’s, Chiquita, Mars, Wal-Mart, and Kraft apparently now all have products certified “sustainable,” sharing, among other things, the little green frog label of the Rainforest Alliance. On the other side of the labeling world, we have Fair Trade, the original product certification initiative aimed at building equitable and sustainable trading partnerships and creating opportunities to alleviate poverty.

Fair Trade and “sustainable” labeling organizations, are private non-profits that have no stockholders, and are therefore not legally obligated to provide information to the public. Combined with the fact that the state lacks the power to ensure that certifiers comply with their own standards, consumers must rely on independent evaluation to assess these labeling initiatives. Can consumers trust that the labels that make our food more expensive actually make a difference?

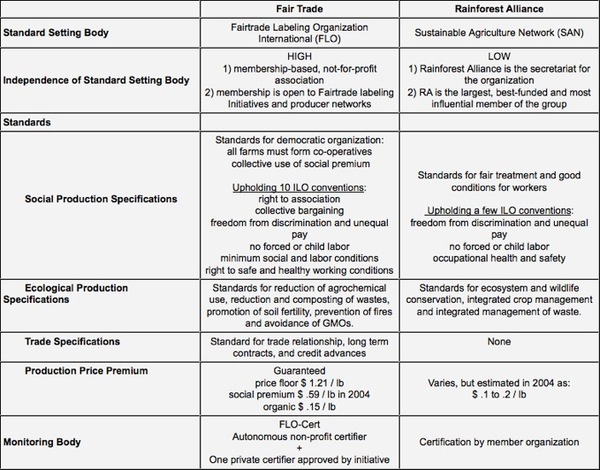

Before we can properly assess the democratic nature of certification, we must understand how these organizations are structured. An ideal initiative has a standard setting body and monitoring body, both completely autonomous. The standard setting body is rather self explanatory; it sets the standards that producers must meet in order to qualify for certification. The standards can be broken down into four separate categories: social, ecological, trade, and price. The monitoring body’s job is at the ground level, assuring that producing farms are honestly run and meet the rigorous requirements.

Rainforest Alliance v. Fairtrade: How Do Their Structures Stack Up?

Relationships to Corporations

“It’s business-driven sustainability.”

– Elizabeth Wenner, director of sustainability for Kraft Foods quoted in Rainforest Alliance’s 2008 Annual Report

Rainforest Alliance & Kraft

Kraft has been a Rainforest Alliance “partner” since 2003. Kraft is listed in Rainforest Alliance’s annual report as a donor that gave between $100,000–$999,999 in 2008 and supported Rainforest Alliance events with more than $10,000 in the same year. Former Kraft executive Annemieke Wijn is a member of the Rainforest Alliance’s Board of Directors.

Such strong financial and structural connections between the corporate purchaser between the standard setting and certification group are a conflict of interest, as

Kraft has obvious incentives to meet its publicly declared purchasing

commitments at the lowest possible cost. It should be of no surprise

that Kraft Foods, Inc. was awarded the Corporate Green Globe Award by

the Rainforest Alliance in 2006.

Rainforest Alliance & Chiquita

To recover from a weakening market position, Chiquita began working

with Rainforest Alliance in 1992 to promote greater corporate social

responsibility. By 2000, all Chiquita bananas grown in Latin American

farms featured Rainforest Alliance’s happy green frog. This was from

all vantage points a good thing, a great step towards minimizing the

social injustices that plague large plantation production in the third

world. In 2002, with the release of “Tainted Harvest: Child Labor and

Obstacles to Organizing on Ecuador’s Banana Plantations” however, the

veil was pulled by Humans Rights Watch. The farms investigated in the

article, farms certified by Rainforest Alliance, relied on child labor,

violated basic labor rights and suppressed attempts at unionization. In

response, Rainforest Alliance went back and re-inspected the

plantations in 2003, but maintained all their certifications.

Standards and Monitoring

Rainforest Alliance sets and enforces its own standard in a closed system. It is the best-funded and largest member of its Sustainable Agriculture Network (SAN). As the SAN secretariate, Rainforest Alliance coordinates the development and review of SAN standards. What about the monitoring body that investigates the producer’s ability to comply with these standards? Well, local certifiers are hired directly by SAN, and certification costs are reduced for farmers who pay travel expenses, lodging, and meals for certifiers.

This is in stark contrast to Fair Trade certifiers including the Institute for Marketing Ecology (Fair for Life) and the Fairtrade Labelling Organization International (TransFair) that follow the requirements of ISO 65, the international quality norm for certification bodies.

Viewed in the most favorable of lights, Rainforest Alliance’s organizational structure does not seem capable the daunting task of curing labor exploitation on large plantations. Structure aside, assuming arguendo that Rainforest Alliance has the ability to enforce their standards, how do those standards compare to Fair Trade?

Fair Trade has standards for farmers’ organizations and for hired labor. Small-scale producers generally must be organized collectively, such as in a co-op, ensuring democratic decision making. Farms with hired labor must allow workers to unionize.

Rainforest Alliance’s standard creation process does not involve the cooperation of farm workers, and are understandably much more lax. RA sets no baseline premium for wages, and at best maintains the low bar set by local governments. In RA’s list of criteria, only those considered ‘critical’ (of which freedom of association is not one of them) must the producer comply, and then by only 50%. The most surprising element of RA standards, given their fundamentally weaker nature to begin, is that a purchaser’s product need only contain 30% certified content to be awarded the green frog label. Given all these percentages, a ‘non-critical’ criteria can be ignored, and final certified product could contain 30% materials that are 50% child labor free. (For a more detailed investigation into RA’s deficient standards, follow this link to a previous OCA article.)

For a final difference, Rainforest Alliance does not charge corporate purchasers for the use of their labels (ostensibly not counting the likely donation requirement), while some Fair Trade Labeling Initiatives charge licensing fees on some products. The fee goes to promote fair trade products, standards development, inspection, among other overhead related costs.

;

Sources

Examining the Rainforest Alliance’s Agricultural Certification Robustness, by Feliz Ventura, Graduate School of International Relations and Pacific Studies, University of California, San Diego

Regulating sustainability in the coffee sector: A comparative analysis of third-party environmental and social certification initiatives, Laura T. Raynolds, Douglas Murray and Andrew Heller

Sociology Department, Colorado State University, Clark Building, Fort Collins, Colorado, USA

Standards and Sustainability in the Coffee Sector, By Stefano Ponte, Senior Researcher, Danish Institute for International Studies