The External Costs of Food

Most people, when asked the cost of something, would answer with a monetary figure based on how much money it would take to buy that thing.

Well, that won’t do for economists, and it won’t do for us in this issue of The Natural Farmer. From an economist’s perspective, that is simply its market price. The true cost may be far less or far more than the market price. The difference, costs not included in the market price, are called external costs, or “externalities”. An externality is “a cost or benefit not transmitted through prices that is incurred by a party who did not agree to the action causing the cost or benefit”. General types of externalities associated with food include ecological effects, environmental quality, greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, animal welfare, social costs associated with labor, and public health effects.

May 1, 2015 | Source: The Natural Farmer | by Jack Kittredge

Most people, when asked the cost of something, would answer with a monetary figure based on how much money it would take to buy that thing.

Well, that won’t do for economists, and it won’t do for us in this issue of The Natural Farmer. From an economist’s perspective, that is simply its market price. The true cost may be far less or far more than the market price. The difference, costs not included in the market price, are called external costs, or “externalities”. An externality is “a cost or benefit not transmitted through prices that is incurred by a party who did not agree to the action causing the cost or benefit”. General types of externalities associated with food include ecological effects, environmental quality, greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, animal welfare, social costs associated with labor, and public health effects.

To take an extreme example of food with a high external cost, consider wheat produced in Oklahoma during the drought of the mid-1930s. Settlers a generation before had plowed up the prairie, exposing the rich, 6-foot deep topsoils. During a few years of rain and relatively high wheat prices during World War I this cropping strategy was handsomely rewarded. But the war ended, wheat prices fell, the topsoil carbon was oxidized into carbon dioxide, and when drought returned the soil dried into dust and blew away, darkening the skies as far away as Chicago and New York. What little wheat was able to be grown in Oklahoma during the Dust Bowl had a low market price. But it had a huge external cost. The federal government had to come in and buy up millions of acres of marginal prairie to keep it out of production and artificially subsidize the remaining farmers so they would convert their fields back into prairie. The cost of that wheat was far higher than its price and the American people, who had no hand in planting wheat in the prairie, picked up that cost as an externality.

It may seem pretty daunting to try to estimate the various external costs or benefits of any economic operation. It is. But without including those externalities, how can we accurately evaluate decisions or make public policy?

How about an externality where we are looking at benefits? What is a good example of that?

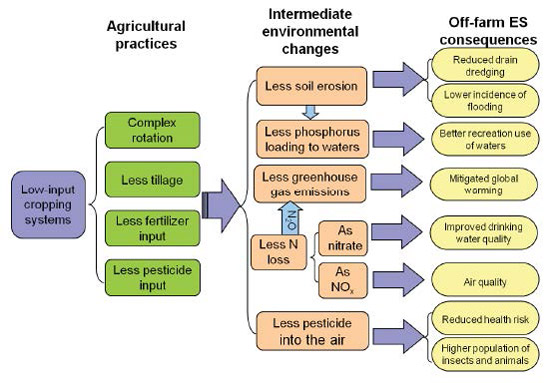

Try going from a conventional chemical farming operation to a low-input or organic one. The farmer may adopt changes such as a more complex rotation to get ahead of weeds, pests, or disease, less tillage to preserve biodiversity and soil carbon, less synthetic fertilizer and more dependence on minerals broken down by soil biology, and less poisons – again to preserve soil life and allow them to be harnessed to enhance plant health.

Those changed agricultural practices have consequences. Less soil is eroded because of lessened tillage and as a result less phosphorus runs off in surface water. Reduced tillage and fertilizer use results in reduced nitrogen loss as both nitrates and nitrous oxide, leading to lower greenhouse gas emissions. And cutting pesticide use results in less polluted air, water and soil. What are the ultimate consequences of reducing inputs? Off-farm you get better flooding control and drainage from less erosion, cleaner water from less pollutants, mitigated global warming because of reduced greenhouse gases, cleaner and safer air from the use of fewer emissions and toxins.

These externalities benefit all of society (all living organisms, really) not just the people who made the farming management changes.

Economists have developed ways of putting dollar figures on these external costs or benefits. These methods are better covered in a graduate course on economics than here. But, basically, they flow from the costs of repairing damages resulting from the initial activity. Or, in the case of benefits, counting costs not incurred (and thus saved) because damage was prevented.

The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations has developed these “full cost accounting” (FCA) methods to look at the disturbing reality that one third of all food produced in the world is wasted. This is either because of its failure to reach the market, or, especially in developed countries, because it is discarded unconsumed after purchase.