GMO Labels Spread as U.S. Congressional Effort to Halt Them Fades

Even as General Mills Inc and other companies vow to keep fighting mandatory labeling of genetically modified food ingredients, they have begun rolling out these disclosures across the United States to comply a new Vermont law.

The moves come as U.S. lawmakers are unlikely to derail Vermont's law requiring labels on foods made with genetically modified organisms, or GMOs, before it takes effect on July 1. The law sets fines of $1,000 per day per product for noncompliance.

March 28, 2016 | Source: Reuters | by Lisa Baertlein

Even as General Mills Inc and other companies vow to keep fighting mandatory labeling of genetically modified food ingredients, they have begun rolling out these disclosures across the United States to comply a new Vermont law.

The moves come as U.S. lawmakers are unlikely to derail Vermont’s law requiring labels on foods made with genetically modified organisms, or GMOs, before it takes effect on July 1. The law sets fines of $1,000 per day per product for noncompliance.

“We can’t label our products for only one state without significantly driving up costs for our consumers, and we simply will not do that,” General Mills recently said on its blog.

Earlier this month, the U.S. Senate blocked a bill that would nullify state laws requiring GMO labels and leave such disclosures to the discretion of manufacturers. A similar bill stalled last year.

The stakes are extraordinarily high for “Big Food,” which depends on ingredients such as corn and soybeans that have been engineered to produce genetic traits such as resistance to insects and pesticides.

The United States is the world’s largest market for GMOs, which are in the vast majority of packaged foods made there. More than 90 percent of the nation’s corn and soybean production is GMO. The combined value of those GMO crops came to $77.6 billion in 2015.

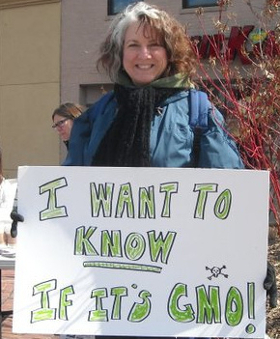

The $363 billion U.S. packaged food industry worries that consumers will shun food containing GMOs, forcing manufacturers to switch to more costly, traditional ingredients. Label advocates describe GMO products as “frankenfoods” and say consumers deserve to know what they are eating.

One food industry representative, who requested anonymity, said Senate attention had waned after the bill’s failure and that there was a lack of consensus over how to proceed.

Republican Senator Pat Roberts of Kansas, who sponsored this session’s bill to stop Vermont’s law, has said he would keep fighting, but he acknowledged the challenge of forging a deal this year.

“The unwillingness to compromise by Senate opponents to my bill is about to hit both farmers and consumers directly in the pocketbook,” Roberts said in a statement.

Coalition for Safe and Affordable Food spokeswoman Claire Parker also said the odds this year were against a solution palatable to her group, which represents food and biotech seed industry efforts to stop mandatory GMO labeling.

“The Senate is in danger of ceding control of labeling for a nation of 300 million to a state of only 600,000 people,” Parker said.

Meanwhile, General Mills, Campbell Soup Co, Kellogg Co, ConAgra Foods Inc and Mars said they were adding GMO labels to their product packaging.

The industry is still fighting the Vermont law in federal court. Its lawyers argued their case before the 2nd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in October, and a decision could come before July 1.