Prions Detected in Eyes of Patients with Brain Disease

Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) is a fatal brain disorder that destroys brain cells, causing tiny holes in the brain. Symptoms of CJD are ataxia, or difficulty controlling body movements, abnormal gait and speech, and dementia. The disease is always fatal and has no cure. CJD is one of several transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs).

December 19, 2018 | Source: Mercola.com | by Dr. Joseph Mercola

Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) is a fatal brain disorder that destroys brain cells, causing tiny holes in the brain. Symptoms of CJD are ataxia, or difficulty controlling body movements, abnormal gait and speech, and dementia. The disease is always fatal and has no cure.1

CJD is one of several transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs). These are a family of progressive neurodegenerative disorders affecting animals and humans. Bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), also known as mad cow disease, presents in much the same way as CJD.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a regulation in 2009 banning specific proteins in feed to prevent the spread of BSE.2 However, the regulation superficially addresses the issue. For instance, slaughterhouse waste products continue to be recycled into bone and blood meal as additives to livestock and pet foods.3

This increases the risk of livestock acquiring BSE as it has proven to be a foodborne-derived disease,4,5 and eating beef from cows with BSE triggers a variant of CJD.6

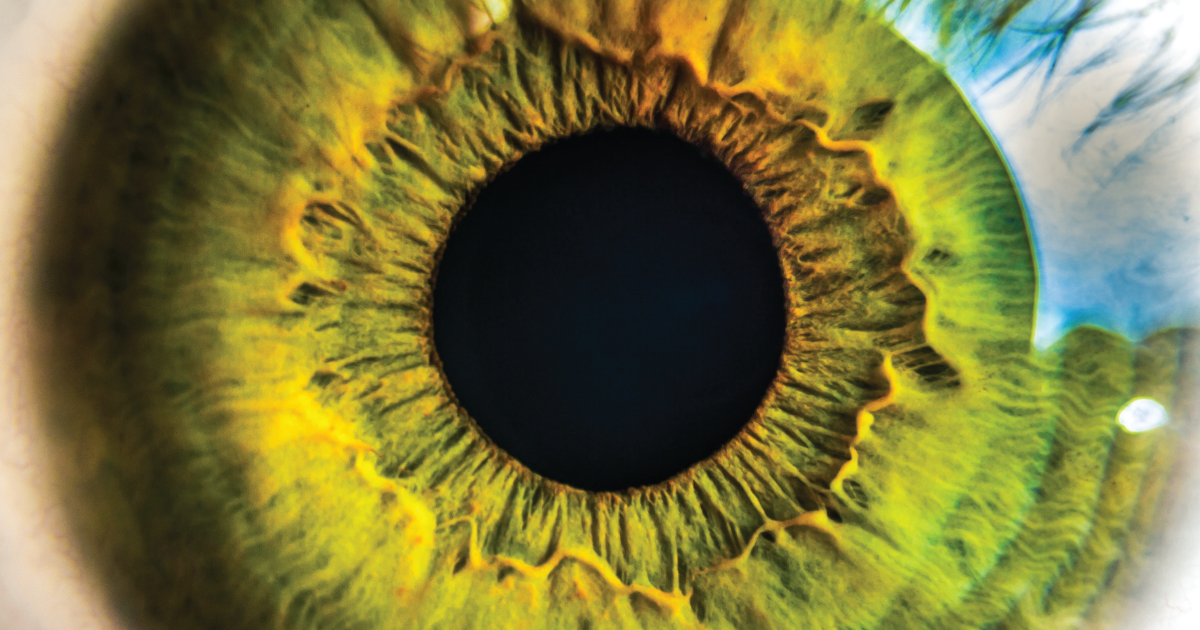

CJD is difficult to diagnose, as taking a brain biopsy to rule out a disease is impractical. The National Institutes of Health have recently published work from colleagues at the University of California San Diego and San Francisco who have measured the distribution and levels of prions in the eye.7

Prions in the Eyes May Indicate Brain Disease

Prions are abnormal forms of proteins collecting in brain tissue and causing cells to die. This leaves sponge-like holes in the brain. BSE and CJD are the result of a prion infection that is untreatable and always fatal.

Byron Caughey, Ph.D., from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, collaborated with researchers from Nagasaki University and developed a method to test brain and spinal cord fluid for the presence of prions in an effort to improve diagnosis of CJD in a clinical setting.8

Dr. Christina J. Sigurdson, professor of pathology at UC San Diego and Davis was on the team, and commented on the problems associated with sporadic CJD (sCJD), a form appearing without known risk factors and accounting for nearly 85 percent of diagnosed cases:9,10

“Almost half of sCJD patients develop visual disturbances, and we know that the disease can be unknowingly transmitted through corneal graft transplantation. But distribution and levels of prions in the eye were unknown.

We’ve answered some of these questions. Our findings have implications for both estimating the risk of sCJD transmission and for development of diagnostic tests for prion diseases before symptoms become apparent.”

The technique, called real-time quaking-induced conversion (RT-QuIC) is currently in use. More recently, Caughey and colleagues attempted to use the same technique to measure the distribution and level of prions in the eye. They recruited 11 people with known CJD and six with other types of fatal diseases to serve as controls. All agreed to donate their eyes for post-mortem analysis.

The researchers found evidence of prions throughout the eyes of the 11 people with CJD but not in the six control patients. This discovery suggests eye tissue may be another avenue for early diagnosis of CJD and raises the question of whether prions may be transmitted through a clinical eye procedure if the instruments or transplanted tissues have been contaminated. Caughey comments:11

“By testing various components of the eye with the RT-QuIC assay, we found that prions can collect throughout the eye — including the fluid inside the eye.

Our findings suggest that we may be able to develop methods of detecting prions in eye components even before symptoms develop, which may help prevent unwitting transmission of prions to others through contaminated medical instruments or through donor tissue.”

Prion Diseases Are Transmissible Between Animals and Humans

Some prion diseases are transmissible between humans and animals. Chronic wasting disease (CWD) is a form of BSE affecting deer, elk and moose. Infected animals may take up to one year to develop symptoms including drastic weight-loss, stumbling and other neurological symptoms, often dying within three years.

The Quality Deer Management Association12 mapped out the number of hunters who killed whitetail deer in four Wisconsin counties with the highest incidence of CWD in the state. The organization believes hunters from 49 states killed deer in this Wisconsin CWD hotbed in the 2016-2017 deer season.

Of the 32,000 deer killed, 22,291 were tested, finding 17 percent positive. By extrapolating data, the researchers estimate approximately 5,000 of those untested were also positive.

Most deer with CWD appear healthy. Hunters transporting carcasses across state lines were breaking regulations in many states now banning the importation of specific animal parts to prevent CWD from entering their state.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the World Health Organization (WHO) recommend testing all deer carcasses and waiting for the all-clear before you eat the venison. If the deer tests positive, it should be safely discarded.13

Previous research14 noted a close similarity between human and rodent prion proteins shown to be protease resistant and infective. The researchers hypothesized that since rats and mice are known to be susceptible to prion diseases, ingestion of infected parts, potentially droppings, could be a mode of transmission of BSE to humans, resulting in CJD.

Eating beef infected with mad cow — which, again, is very similar to CWD — is known to cause CJD in humans. Symptoms are similar to Alzheimer’s and include staggering, memory loss, impaired vision, dementia and, ultimately, death. Between 2002 and 2015, the prevalence of CJD rose by 85 percent across the U.S. In 2015, there were 481 cases.15

The first case of CWD was recently diagnosed in reindeer in Norway, which researchers theorized may have occurred when bottled North American deer urine was transported for use as a lure. In an effort to eradicate the disease before it spread, an advisory panel for the Norwegian Scientific Committee for Food Safety recommended the entire herd be culled.16