The Truth About COVID-19 ‘Long-Haulers’

You may have seen reports about COVID-19 patients who seem unable to fully recover. Some complain of lingering chronic fatigue symptoms. Others struggle with mental health problems. In fact, a study from Oxford University published online November 9, 2020, in The Lancet Psychiatry, found 18.1% of individuals diagnosed with COVID-19 also received a first-time psychiatric diagnosis in the 14 to 90 days afterward.

November 20, 2020 | Source: Mercola.com | by Dr. Joseph Mercola

You may have seen reports about COVID-19 patients who seem unable to fully recover. Some complain of lingering chronic fatigue symptoms. Others struggle with mental health problems.

In fact, a study1,2 from Oxford University published online November 9, 2020, in The Lancet Psychiatry, found 18.1% of individuals diagnosed with COVID-19 also received a first-time psychiatric diagnosis in the 14 to 90 days afterward. Most common were anxiety disorders, insomnia and dementia. A similar trend was also observable after COVID-19 relapses.

Interestingly, people with pre-existing mental illness were also found to be 65% more likely to be diagnosed with COVID-19 than those who did not have a pre-existing psychiatric problem.

Now, while this may sound terrifying, I would point out that, given the fearmongering surrounding COVID-19, it’s not surprising that receiving a diagnosis would trigger anxiety and insomnia in many. It doesn’t mean you end up with a chronic psychiatric disorder. It just tells us that getting a COVID-19 diagnosis is very stressful, even if you remain asymptomatic.

The link to dementia is interesting, however, and likely needs to be looked into further. This also applies to the higher risk of COVID-19 if you have a pre-existing mental health problem. It’s possible that people struggling with depression, anxiety and similar disorders are simply more likely to get tested for COVID-19 — and end up receiving false positive diagnoses.

As discussed in “Asymptomatic ‘Casedemic’ Is a Perpetuation of Needless Fear,” mass testing of asymptomatic people doesn’t tell us anything of value since the test cannot discern between an active infection and the presence of nonreproductive (harmless) virus. It only makes the pandemic appear graver than it is.

That said, going through a severe bout of COVID-19 is also going to take a mental toll. As reported3 by a 40-year-old previously healthy man who underwent an apparent recurrence of COVID-19, after three weeks of fatigue, he started feeling “completely overwhelmed” and for the next 72 hours, he “felt unwell in a way that was bordering on not coping.”

He says he “felt physically exhausted” and “mentally drained.” Severe illness will do that. He says it took him nearly eight weeks before he started feeling “close to my normal self again,” but even then, he still struggled with “fatigue to the point of having to sleep in the day” and an inability to exercise.

COVID-19 ‘Long-Haulers’

He’s not alone in reporting such symptoms. An estimated 10% of patients treated for COVID-19 report fatigue, breathlessness, brain fog and/or chronic pain for three weeks or longer.4 This phenomenon occurs even among patients who had mild cases of COVID-19.

U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data5 show the rate of COVID-19 patients who continue experiencing lingering health problems after recovering from acute COVID-19 may be as high as 45%. Only 65% report having returned to their previous level of health within 14 to 21 days after receiving a positive test result.

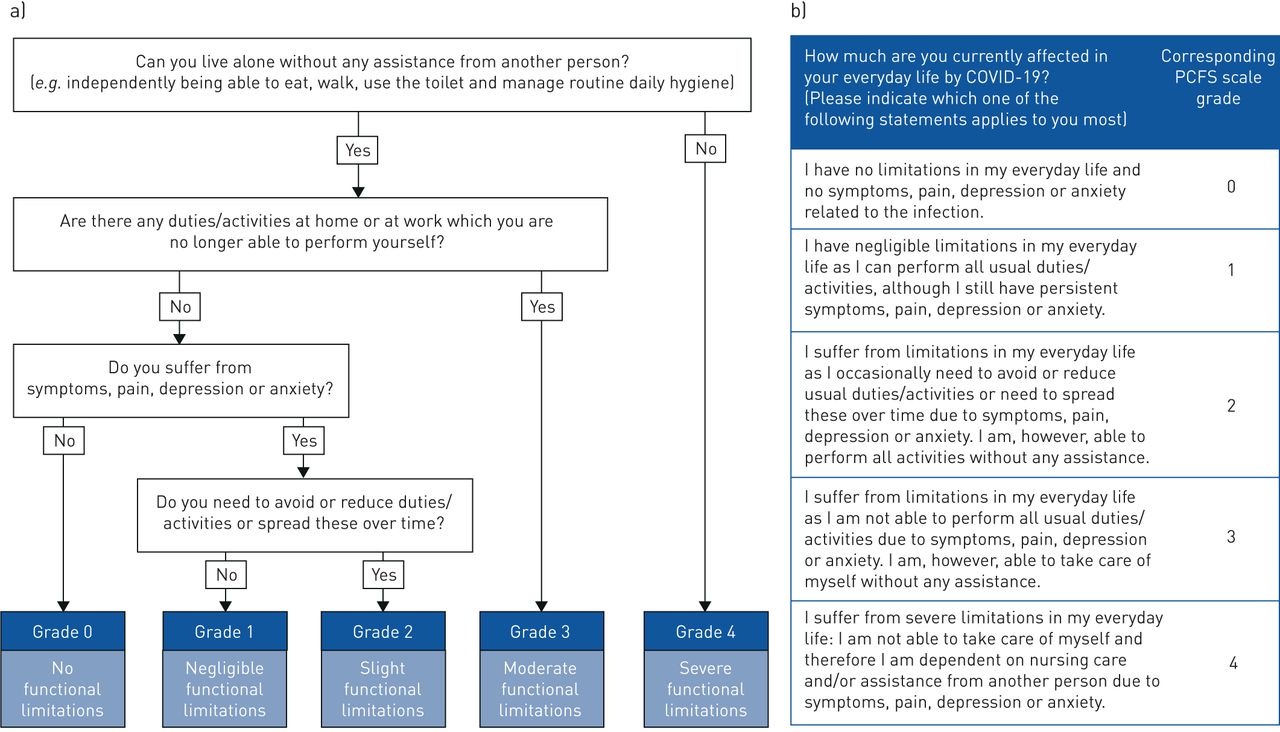

The flowchart6 below, published in the European Respiratory Journal, is a tool you can use to measure your functional status over time after recovery from COVID-19.

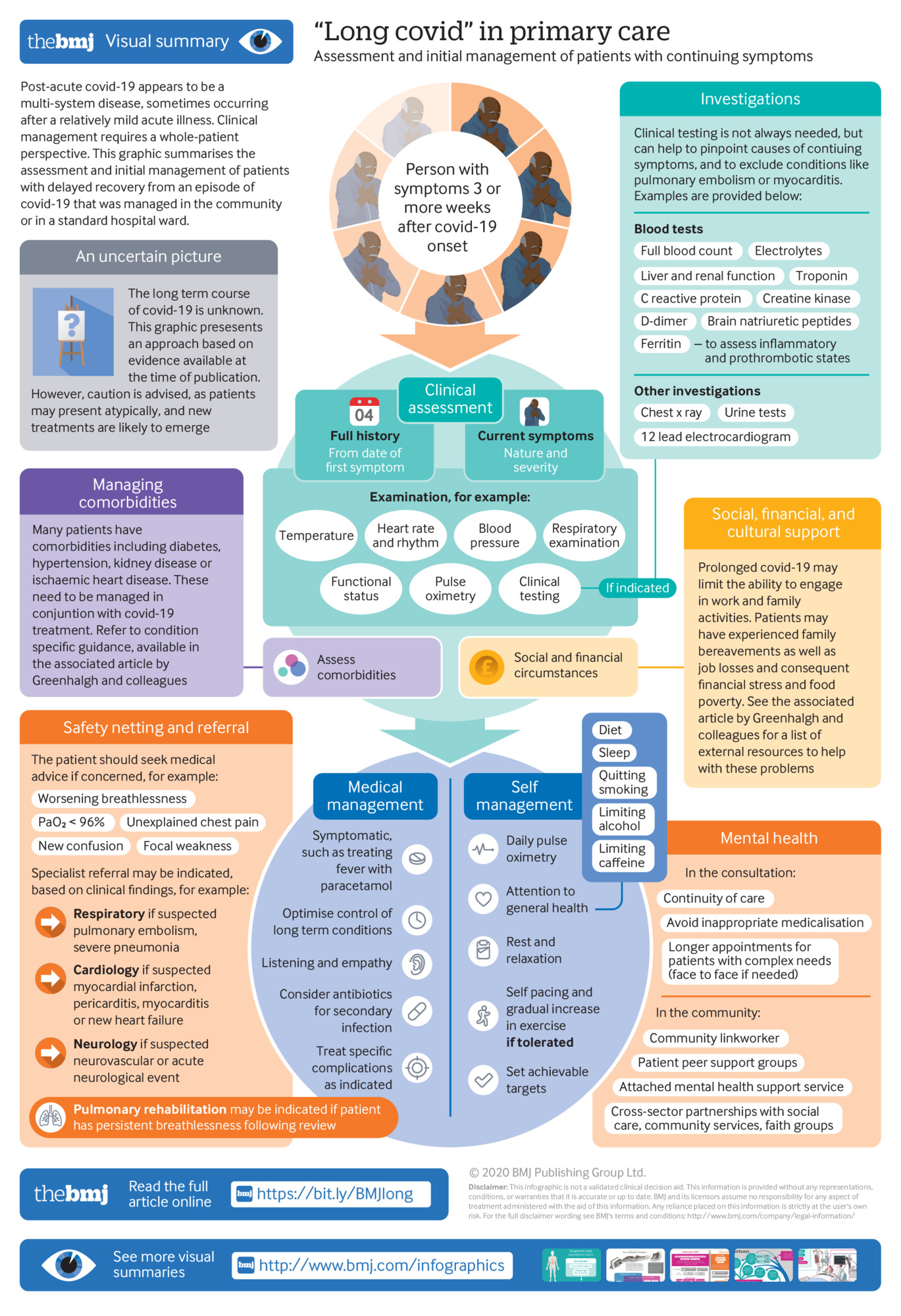

Treatment Guidance for Post-Acute COVID-19

The good news is that, according to an August 11, 2020, article in The BMJ,7which provides post-acute COVID-19 primary care guidance, many of these “long COVID” patients do spontaneously recover — albeit slowly — “with holistic support, rest, symptomatic treatment and gradual increase in activity.” To support recovery, the article suggests that:8

“… patients should be managed pragmatically and symptomatically with an emphasis on holistic support while avoiding over-investigation. Fever, for example, may be treated symptomatically with paracetamol or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Monitoring functional status in post-acute COVID-19 patients is not yet an exact science. A post-COVID-19 functional status scale has been developed pragmatically but not formally validated9 …

Referral to a specialist rehabilitation service does not seem to be needed for most patients, who can expect a gradual, if sometimes protracted, improvement in energy levels and breathlessness, aided by careful pacing, prioritization, and modest goal setting.

In our experience, most but not all patients who were not admitted to hospital recover well with four to six weeks of light aerobic exercise (such as walking or Pilates), gradually increasing in intensity as tolerated. Those returning to employment may need support to negotiate a phased return.”

The following graphic from that BMJ article10 provides a visual summary of the recommended assessment and management recommended for patients with lingering symptoms after recovering from acute COVID-19.