Where Did the Antiwar Movement Go?

Let me tell you a story about a moment in my life I’m not likely to forget even if, with the passage of years, so much around it has grown fuzzy. It involves a broken-down TV, movies from my childhood, and a war that only seemed to come closer as time passed.

My best guess: it was the summer of 1969. I had dropped out of graduate school where I had been studying to become a China scholar and was then working as a “movement” printer -- that is, in a print shop that produced radical literature, strike posters, and other materials for activists. It was, of course, “the Sixties,” though I didn’t know it then.

August 11, 2015 | Source: Tom Dispatch | by Tom Engelhardt

Let me tell you a story about a moment in my life I’m not likely to forget even if, with the passage of years, so much around it has grown fuzzy. It involves a broken-down TV, movies from my childhood, and a war that only seemed to come closer as time passed.

My best guess: it was the summer of 1969. I had dropped out of graduate school where I had been studying to become a China scholar and was then working as a “movement” printer — that is, in a print shop that produced radical literature, strike posters, and other materials for activists. It was, of course, “the Sixties,” though I didn’t know it then. Still, I had somehow been swept into a new world remarkably unrelated to my expected life trajectory — and a large part of the reason for that was the Vietnam War.

Don’t get me wrong. I wasn’t particularly early to protest it. I think I signed my first antiwar petition in 1965 while still in college, but as late as 1968 — people forget the confusion of that era — while I had become firmly antiwar, I still wanted to serve my country abroad. Being a diplomat had been a dream of mine, the kind of citizenly duty I had been taught to admire, and the urge to act in such a fashion, to be of service, was deeply embedded in me. (That I was already doing so in protesting the grim war my government was prosecuting in Southeast Asia didn’t cross my mind.) I actually applied to the State Department, but it turned out to have no dreams of Tom Engelhardt. On the other hand, the U.S. Information Agency, a propaganda outfit, couldn’t have been more interested.

Only one problem: they weren’t about to guarantee that they wouldn’t send a guy who had studied Chinese, knew something of Asia, and could read French to Saigon. However, by the time they had vetted me — it took government-issue months and months to do so — I had grown far angrier about the war, so when they offered me a job, I didn’t think twice about saying no.

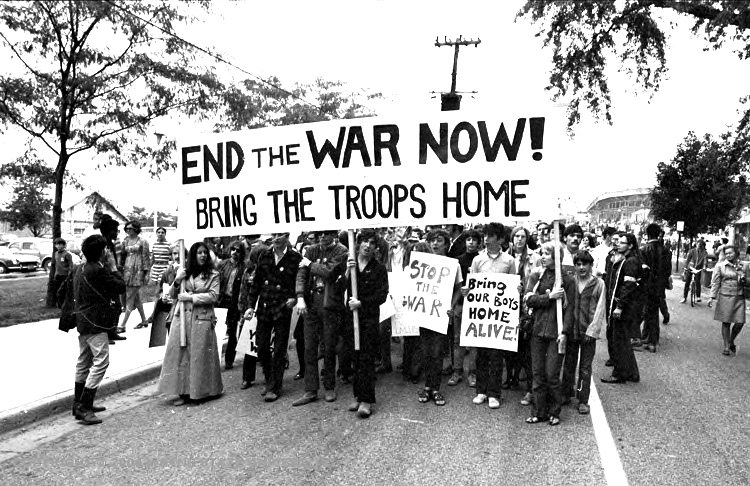

Somewhere in that same year, 1968, I joined a group called the Resistance and in an elaborate public ceremony turned in my draft card to protest the war. For several years, I had been increasingly involved in antiwar activism, had marched on the Pentagon in the giant 1967 processional that Norman Mailer so famously recorded in Armies of the Night, and returned again a year or two later when, for the first time in my life, I got tear-gassed.

For a while, I had also been working as a draft counselor with a group whose initials, BDRG, I remember. A quick check of Google tells me that the acronym stood for the Boston Draft Resistance Group. Somewhere in that period, I helped set up an organization whose initials I also recall well: the CCAS. Though hardly an inspired moniker, it stood for the Committee of Concerned Asian Scholars. (That “concern” — in case it’s not clear so many years later — involved the same war that wouldn’t end.) With a friend, I designed and produced its bulletin. As one of those “concerned scholars,” I also helped write a group antiwar book, The Indochina Story, which would be put out by a mainstream publishing house.

Of course, there’s much that I’ve forgotten and I can’t claim that all of the above is in perfect order. Even at the time, life was a blur of activism. Nearly half a century later, I’m a failing archive of my own life and so much seems irretrievable.

My intention here, however, is simply to offer a sense of how so many lives came, in part or in whole, to revolve around that war, while other things went by the wayside. It’s true that our government hadn’t mobilized us, but we had mobilized ourselves. Though much has been written about “dropping out” in the 1960s, this antiwar form of it has been far less attended to.